Quantum computing. Why exactly?

Lothar Borrmann

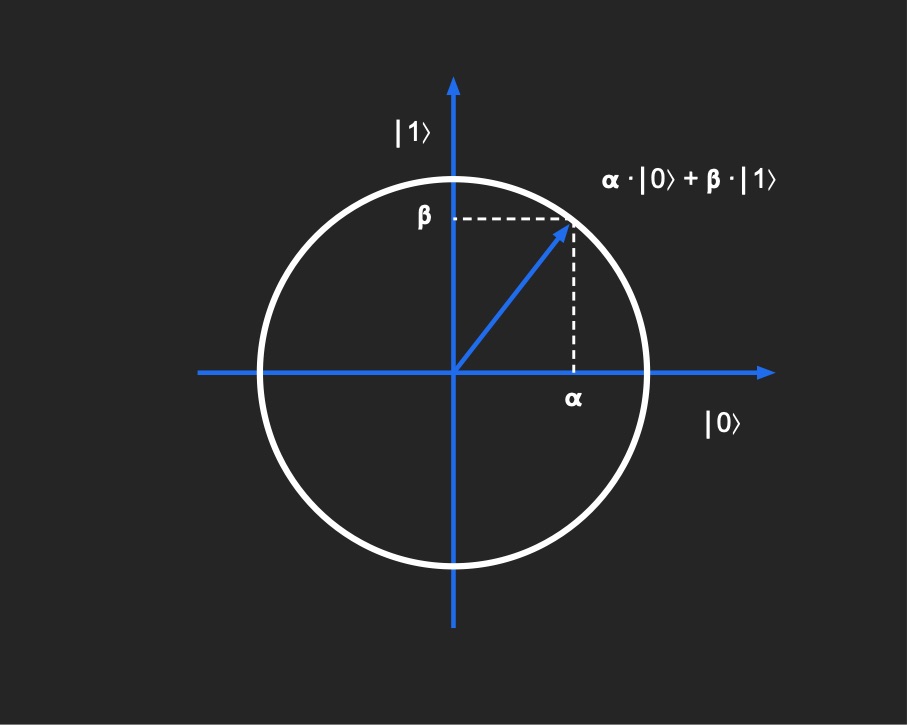

The superposition as a vector

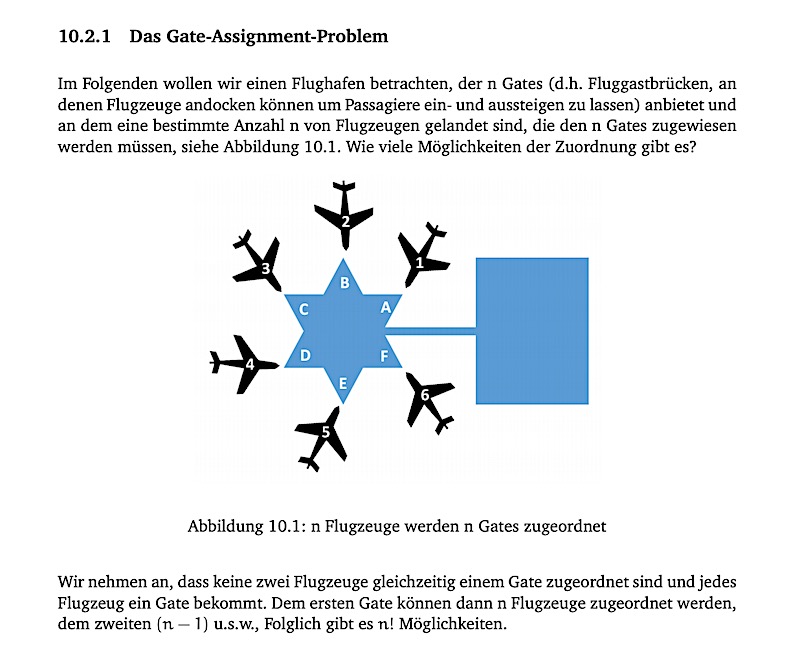

Over the last sixty years or so, the performance of classical digital computers has continued to increase – Gordon Moore sends his regards! In the meantime, however, we are reaching physical limits. Despite all the performance, there are quite a few problems, e.g. in optimization, that our computers cannot really calculate. So far, we have been content with approximations.

In this context, we can only progress if there is a paradigm shift.

Quantum computers (QC) are just such a paradigm shift. Their functionality is not based on bits with a deterministic value of 0 or 1, but on qubits. A qubit is a basic unit of information that can only be correctly described by quantum mechanics and can have different states at the same time – superposition. And along with another quantum physics phenomenon, entanglement, information can be exchanged.

The function of a computer based on this is radically different from what we are used to from computers. And therein lies the advantage. As early as 1994, Peter Shor developed an algorithm for prime factorization on quantum computers showing that they can be used to calculate tasks considered insolvable on conventional computers, that would take years or decades to solve.

So quantum computers will not replace smartphone processors, PCs, or the Linux cloud server. But they do promise a breakthrough when it comes to dealing with very specific problems.

There are now two challenges for the productive use of such systems: Firstly, the construction of a quantum computer with a sufficient number of reliable qubits – i.e., the hardware – and secondly, the programming of such a computer, which follows completely different principles than traditional software.

Many players have been competing to develop the hardware since around 2015, from startups to Google to IBM. And, as is usually the case with such new and immature technologies, very different approaches are being pursued.

However, the use of such experimental machines, even if they are accessible in the cloud, is almost exclusively open to researchers and experts. Therefore, the QAR-Lab focuses on the comparative validation of such different QC architectures, on the development of quantum software, and on solving real-world problems in order to offer users a migration path.

Quantum software encompasses a broad spectrum from hardware-related QC compilers, QC circuits, and QC algorithms to full QC applications. These include, in particular, algorithms that use essential characteristics of quantum mechanics such as superposition or entanglement in the calculation or solving of problems so they can run on quantum computers.